Back in 2020 I put together a little blog post discussing some of the recent optimisations I’d made to ComputerCraft’s monitor renderer1. After that work, I was fairly sure of two simple facts:

- VBOs (or rather VBO uploading) was always going to be slow.

- TBOs were as fast as they were getting.

Unfortunately for my ego (though fortunately for your FPS), both of these have turned out to be wrong! Last year2 CC: Restitched contributor toad-dev and I had another look at everything, and made a few more improvements.

Let’s talk about depth blockers

While the previous post talked quite a bit about how we render monitors, there were a couple of things we glossed over. Let’s remedy that now:

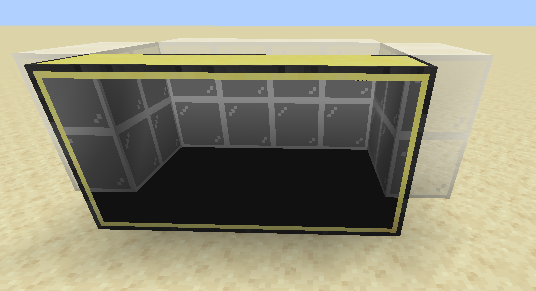

ComputerCraft (and thus CC: Tweaked) renders monitors in a series of layers:

- The background colours of each cell.

- The characters in each cell.

- The cursor (this blinks on and off, so we don’t want to bake it into our buffer).

While its helpful to conceptualise these layers as sitting on top of each other, we still want them to be on the same plane in 3D space. However, doing this leaves us especially prone to an effect known as z-fighting, where objects phase through each other, as the graphics card can’t decide which one is in front.

To avoid this, we do a sneaky trick and turn off writing to the depth buffer while rendering the monitor. This means that the different layers of the monitor won’t fight with each other. However, after we’ve finished drawing the monitor, we must render one final quad which just writes to the depth buffer, to make sure the monitor doesn’t end up accidentally transparent.

While this has served us well for a long time, it doesn’t work with many optimisation and shader mods. Thankfully, it turns out there’s a much easier way to resolve the problem of z-fighting, which is both shader-compatible and a tiny bit more efficient.

Remember that z-fighting is caused by trying to render multiple objects on the same plane. The obvious fix here is just “don’t do that” and instead shift each layer to be a tiny bit in front of the previous one.

We’d actually tried this before, by shifting each layer a tiny amount in world space (the coordinate system relative to the world itself). One can imagine this as drawing the text floating a few millimetres in front of the monitor. Alas, this can end up looking very odd, especially when you view the monitor very closely or from the side!

The correct solution here is to offset each layer in camera space, effectively moving the characters a tiny amount towards the camera/player3. This has the same effect as offsetting in world-space, but without any of the odd artefacts.

This is a douple win: we’ve reduced the number of draw calls (no longer need the extra depth quad), and we’ve got better compatibility with other mods. Yay!

Speeding up the cursor

Let’s turn our eyes to the cursor. As alluded to earlier, the cursor blinks on and off multiple times a second, so we don’t want to bake it into the TBO or VBO, as we’d have to rebuild them every time the visibility changed! Instead, we draw the cursor separately to the monitor contents.

Unfortunately, doing this is not without its downsides, as we now need to do another buffer upload and draw call every frame. It’s not much, but when you’ve a few hundred monitors, it can take a few milliseconds per frame, eating up valuable time.

Thankfully, it turns out we don’t need to do this in a separate pass at all. There’s some neat tricks we can apply instead:

For the TBO renderer, we can just do everything in the shader! We store the cursor position and visibility as part of the buffer, alongside the main monitor contents. The global cursor blink state is placed in a uniform, as it can be shared across all monitors. Inside the shader, we can then read all this information and composite the cursor on top of the rest of the monitor:

// Read the cursor texture.

vec4 cursorTex = recolour(texture(Sampler0, (texture_corner(95) + pos) / 256.0), CursorColour); // 95 = '_'

// If CursorPos == cell, composite the cursor texture on top of the character.

vec4 img = mix(charTex, cursorTex, cursorTex.a * float(CursorBlink) * (CursorPos == cell ? 1.0 : 0.0));

// Then mix in the background colour.

vec4 colour = vec4(mix(Palette[bg], img.rgb, img.a * mult), 1.0) * ColorModulator;For the VBO renderer, we employ a very different approach. One thing to remember about VBOs is that while they store a list of vertices to draw, you don’t have to draw everything in that buffer. This means we can add the cursor to the end of the main VBO, and simply chose not to render it on some frames.

After these changes, drawing a TBO only performs one draw call, and drawing a VBO performs two. Again, the changes here are tiny (a few microseconds per monitor), but it all adds up. Well, a tiny bit at least!

Building buffers the Unsafe way

So far we’ve been talking about the render calls we make on every frame, namely when the monitor has not changed. When the monitor has changed we need to regenerate a buffer and send it to the GPU. While this happens less often, the performance is still very important. Indeed, faster buffer uploading was one of the reasons we prefer TBOs over VBOs!

Well, it was. Alas, for reasons which are a mystery to me, when I did the initial work on TBOs, I never sat down and actually profiled the code. While I could see that the FPS was higher under TBOs compared with VBOs, I never dug into why.

If only I had: my assumption was that the slow portion of the code was sending the vertex data to the GPU, but no! Instead, it lies inside our function to add a quad to our buffer:

private void drawQuad(VertexConsumer consumer, Matrix4f matrix, ...) {

consumer.vertex( poseMatrix, x1, y1, z ).color( r, g, b, a ).uv( u1, v1 ).uv2( light ).endVertex();

consumer.vertex( poseMatrix, x1, y2, z ).color( r, g, b, a ).uv( u1, v2 ).uv2( light ).endVertex();

consumer.vertex( poseMatrix, x2, y2, z ).color( r, g, b, a ).uv( u2, v2 ).uv2( light ).endVertex();

consumer.vertex( poseMatrix, x2, y1, z ).color( r, g, b, a ).uv( u2, v1 ).uv2( light ).endVertex();

}This snippet uses Minecraft’s VertexConsumer class, a friendly API for emitting vertices to a buffer. This abstracts away all of the painful bits of generating a vertex, such as making sure each element is correctly formatted and aligned, and ensuring all elements are present.

However, as you can probably guess, all this extra bookkeeping comes at an additional cost - a cost which really starts to hurt once at larger scales. Updating 120 full-sized monitors in one go takes 300ms, causing the game to run at 3fps.

Ideally we’d just tear out this code and replace it with something faster. Unfortunately there’s still some places, where we need to use a VertexConsumer. We want to avoid duplication as much as possible, so let’s do the Proper Java Thing and introduce some polymorphism.

interface VertexEmitter {

void vertex(Matrix4f matrix, ...);

}

record FastQuadVertex(ByteBuffer buffer) implements VertexEmitter {

// A fast version which writes directly to a ByteBuffer

}

record MinecraftVertexEmitter(VertexConsumer cosumer) implements VertexEmitter {

// A slow version which uses a VertexConsumer as before.

}We define an interface which will handle emitting our vertex, and then provide two implementations. Our monitor code will use the fast version, and our UI code can use the Minecraft-compatible one. This helps us a lot, bringing the frame time down to 60ms (16fps).

Well, sometimes. If you relaunch the game, you might get an entirely different value, varying between 50 and 100ms per frame. To understand why, we really need to get into the weeds of Java’s runtime.

Java and the JIT

As you may know, Java is not compiled to native code. Instead, it’s compiled to Java bytecode, which is then executed by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Once some code has been run enough times, it’s converted into machine code, allowing it to reach near-native (i.e. C or Rust) speeds.

The process of doing this is actually really clever: it’s able to look at how code has behaved so far, and then tries to optimise it for that specific case. For instance, let’s consider a function call to VertexEmitter.vertex:

emitter.vertex(...);As this is a virtual call, normally this would require several additional memory fetches to find which version of vertex we should execute. However, if one particular method is called a lot more than the others, the JVM might be able to optimise it to something like this:

if(emitter instanceof FastVertexEmitter) {

FastVertexEmitter.vertex(emitter, ...);

} else {

emitter.vertex(...);

}This may only help a tiny amount, but as we’re now calling a statically resolvable method, it unlocks other optimisations such as function inlining. This has a bit of cascade effect, allowing even more optimisations to be applied, which can result in significant performance gains.

This is amazing when it works. However, when it doesn’t it’s a bit of a nightmare. What happens if the JVM decides that MinecraftVertexEmitter is the common case? Then we won’t get our extra optimisations, and so our code runs that bit slower. This is exactly what we were seeing earlier!

Irritatingly, there’s not many good solutions here. We can reduce the number of virtual calls we make by changing VertexEmitter to work in terms of quads rather than single vertices (bringing us down to 33ms/frame), but it’s still very variable. The only reliable solution here is making two copies of the terminal rendering code - one specialised for each VertexEmitter.

Micro-optimisations

Specialising gives us a steady 33ms/frame, but that’s a long way from the ideal 16ms/frame we’d need to reach 60fps. However, working out what to do now is quite a bit harder. Pretty much everything is inlined into our drawQuad function, which means that most Java profilers don’t tell us anything useful.

Instead, let’s dig into the machine code that Java is generating for our function, using the fantastic JITWatch. I actually used this earlier when looking into virtual method calls, but it’s much more useful now.

First, let’s look at our new specialised drawQuad method:

private void drawQuad(ByteBuffer buffer, Matrix4f matrix, ...) {

buffer.putFloat(x1);

buffer.putFloat(y1);

buffer.putFloat(z);

// etc for other elements and other vertices

}ByteBuffer.putFloat is quite a simple function4: it just performs a bounds check, writes the value to memory and then increments the position.

public class ByteBuffer {

public void putFloat(float value) {

int pos = this.position;

if(pos + 4 >= this.length) throw new IndexOutOfBoundsException();

Unsafe.putFloat(this.addresss + pos, value);

this.position = pos + 4;

}

}Curiously5, even when function is inlined into drawQuad, the machine code ends up re-reading this.position from memory every time, even though the latest value should already be in a register. We can avoid this by specifying the position as an argument to putFloat:

private void drawQuad(ByteBuffer buffer, Matrix4f matrix, ...) {

int pos = buffer.position()

buffer.putFloat(pos, x1);

buffer.putFloat(pos + 4, y1);

buffer.putFloat(pos + 8, z);

// etc for other elements and other vertices

// Update the position at the end.

buffer.position(pos + 112);

}Doing this takes us down to 20ms/frame (50fps). This is a significant improvement, but we’re not quite there at our target 60fps yet. Unfortunately, there’s nothing else we can legally do - the only thing left is the bounds checks, which the JVM isn’t smart enough to remove.

Unsafe code

Having exhausted all legal options, let’s turn to illegal ones. In this case, we’re going to commits the horrific crime of ignoring Java’s memory guarantees, and just writing to memory directly.

This does sound like a horror story, so we try to keep these writes as localised as possible, and perform some sanity checks up-front.

private void drawQuad(ByteBuffer buffer, Matrix4f matrix, ...) {

var position = buffer.position();

var addr = MemoryUtil.memAddress(buffer);

// Require our writes to be in bounds and aligned to a 32-bit boundary.

if (position < 0 || 112 > buffer.limit() - position) throw new IndexOutOfBoundsException();

if ((addr & 3) != 0) throw new IllegalStateException("Memory is not aligned");

memPutFloat(addr + 0, x1);

memPutFloat(addr + 4, y1);

memPutFloat(addr + 8, z);

// etc for other elements and other vertices

// Update the position at the end.

buffer.position(position + 112);While the code here horrific, my goodness it’s worth it. This ends up being twice as fast as the previous version, only taking 9ms/frame (111fps) to update our 120 monitors. This is comparable to our TBO renderer, which takes about 8ms/frame.

Wow. In total, that’s a 30x speed improvement over our original code. And all it took was for me to look at a profiler :D.

If you’ve not read that, it’s probably worth giving it a quick skim as much of this article won’t make sense!↩︎

This work was done in March/April 2022. I didn’t get round to starting this blog post until September, and only now am finishing it. What can I say, I’m a slow writer!↩︎

We use

glPolygonOffsetfor this. You can do this by manipulating matrices directly, but that’s a bit harder to do in this bit of Minecraft’s rendering code.↩︎This is a lie. The actual implementation is a little more complex, as it needs to take into account resource scopes (part of the new FFI API) and alignment.↩︎

I don’t think this is required under the Java Memory Model, but also not entirely sure.↩︎